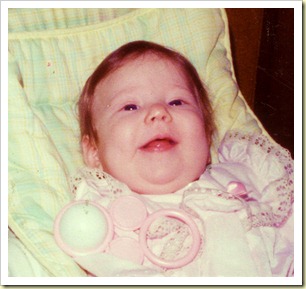

There is compelling evidence that my love of eating began in the womb. I have a newspaper clipping announcing my birth which reads that I "tipped the scales" at eight pounds, four ounces." Additionally, there is a home video, filmed shortly after I was born, where my mom cradles me in her arms as she coyly suggests that she should hold me at a different angle to better disguise my chins.

Loving food is the prerequisite to knowing food. The former asks little more than a willing participant. The latter requires that the eager eater have an open mind and ongoing exposure to the ever-evolving world of food culture. The fact that I grew up in Alaska does much to explain the lag in my transition from food lover to scholar.

Alaska is known for its extremes and the diet of its residents tends to follow suit. One one hand, Alaskans are blessed with an abundance of fresh fish, game and wild berries. On the other, they face hefty markups for perishable foods such as produce, dairy and meat. Although less so than when I was growing up, foods with a shelf life make up the bulk of many shopping carts in the checkout line. Point in case, I had my first fresh asparagus when I was twelve. It took some getting used to as I had long considered the bloated, chartreuse variety a delicacy.

Ignorance did nothing to deter my love of food. The passion that began in the high chair and transitioned to the table was reinforced with my initiation into a family of good cooks. My dad’s father is the son of Yugoslavian immigrants who left their country to eventually settle in Juneau, Alaska. My great grandfather found work in the coal mines. My great grandma Baba, a self-deprecating woman with twinkling eyes and a thick accent , clearly spoke the language of food. She cooked for her family and she loved to eat.

My grandpa and his siblings were brought up observing the ways of ‘the old country’. They spoke the language, wrote to their family back home, and regularly ate the cuisine of their native land. Baba prepared traditional foods such as savory beef and tomato filled cabbages, called sarma, cheese filled crepes, called palacinka, walnut studded dessert bread, known as pita, and rostulas, which are subtly sweet, fried cookies with a dense crumb and a crisp golden exterior. They are dangerously addictive.

Baba’s love of food was personified in her reverence of the connection between table and family. She raised a family of good cooks and instilled in her children the belief that food brings families together. Baba died shortly before I was born but her legacy has lived on through the devotion of her family. During my childhood, we made frequent pilgrimages from Sitka to Juneau, usually by ferry, to take part in family gatherings. These were not timid affairs, mind you; the average attendance hovered around thirty. Regardless of the occasion, food was indubitably the focal point.

Our visits were often timed to coincide with holidays and each occasion had a set of foods to go along with it. Some dishes remained the specialty of one particular family member; whereas others changed hands over the years. Aunt Helen’s homemade crescent rolls were delicate, buttery half moons, with a texture that fell somewhere between that of a brioche and a croissant. Aunt Carol, from Japan, made sushi rolls or a refreshing salad with glassine rice noodles, tart mandarin oranges, briny shrimp and cool cucumbers. Her contributions were the ideal antidote to the richer fare that dominated the table. My great aunties, the baking queens, produced tantalizing cakes, pristine pies and irresistible cookies, known to challenge even the most fervent resolve.

Rumor has it that when I was a few years old, I approached a table laden with Christmas treats, hands clasped behind my back. Salivating, I reached for a cookie and then proceeded to slap my own hand, admonishing myself, saying, “No, Sarah!'”

When my family gathered, we ate together and we ate well, as Baba intended. More often than not, the spread was comprised of traditional American cuisine rather than that of the Eastern European variety. The exception to this was Serbian Christmas, better known as Orthodox Christmas, on January 7. Family members provided a designated dish, which included Aunt Nat’s sarma, Uncle Don’s palachinka’s, Aunt Vi’s rostulas and Aunt Helen’s pita. This immersion into my family’s culture provided me with a respect for my heritage and a budding passion not only for loving food but for getting to know it, as well.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment