The food of my upbringing was defined by two opposing schools of thought. Dad would waltz into the kitchen without a plan and with total disdain for recipes or structured meals. An accountant by day, he left the numbers at work and preferred to put his right brain to use when he cooked. Mom, on the other hand, followed recipes to the letter. She upheld traditions and ran her kitchen like a well-oiled machine. You could see your face in every pot and pan and it was always safe to eat off of her immaculate kitchen floor. She was a ‘Martha’ before her time.

Dad invented ‘salad bar night’ with little bowls full of things like crumbled bleu cheese, bits of bacon, chunks of chicken or turkey, tomato wedges and slices of hard boiled egg. He taught me how to select the perfect avocado. His barbequed steaks were and still are perfection. As accompaniment, he would caramelize onions with mushrooms until they made love to one another, their scent wafting down the hallway into my bedroom, beckoning me to the kitchen. Our island’s limited produce selection never seemed to faze him. He took it as a challenge and he was a fruit and vegetable fiend. Dad would cut granny smith apples in wide slices resembling flat-bottomed boats. For some reason, they always tasted better when he sliced them like that. He once brought home a pomegranate and we marveled as he cracked open its red exterior to reveal the ruby gems of fruit inside. He didn’t care about things like stained fingers. His spontaneity brought food to life. Instead of merely eating our food, we were experiencing it and those memories have resonated long after the flavors have faded away.

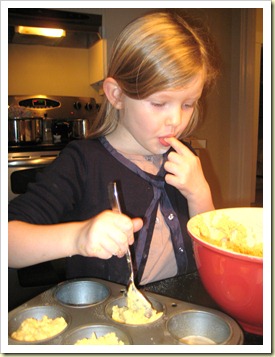

Mom taught me how to bake though, at the time, I had no idea that I was learning. She says that I must have picked up her skills by osmosis as I rarely paid attention from start to finish. I pieced together snippets from the many occasions in which I flitted in and out of the kitchen while she was baking. I loved sitting on the kitchen counter, visiting and usually distracting mom as she measured, sifted and mixed. I can still hear her lilting voice, reading the recipe aloud to herself so as not to lose focus. I occasionally measured ingredients or cracked open an egg but I learned more about baking from watching. I tucked away a mental archive of the way the ingredients looked, mid-recipe: the white luster of creamed sugar and butter, the thin, juicy slices of peeled apple mixed with cinnamon and sugar, those perfectly symmetrical spheres of cookie dough on a tray destined for the oven… At every stage, there was something to see, smell or anticipate. I once read that, at a famous French culinary institute, they encourage their students to “goutez, goutez, goutez!” which is French for “taste, taste, taste!” I can attest to this because I never missed an opportunity to sample along the way and I know that my baker’s equilibrium is better for it. Mom always says, “The secret of a good baker is that everything tastes better when you bake it with love.” I would add that the other secret is having a very gifted teacher.

These days, I enjoy baking with my daughter, Annabelle. She can be as inattentive as I once was but I suspect that, like her mother, she absorbs more than she lets on. And already, she is an expert taster.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

que sera sera

Sunday, March 28, 2010

so deer to my heart

If mom was the cautious cook, then dad was the unabashed daredevil of our kitchen. What he lacked in culinary prowess, he made up for in gusto. His enthusiasm, although occasionally dampened by mom's reserve, was contagious. Luckily for dad, I served as the willing antidote to mom's reluctance to try new foods.

Living in Alaska was undeniably different from life 'in the lower 48' or 'down South' as Alaskans like to refer to the rest of the United States. This was further defined by my growing up on a small island with a population that hovers around 8,000. The town has a span of fourteen miles of driving road, from end to end, and boasts a rich history involving the Tlingit Indians and Russian royalty duking it out long before the Alaskan territory was known as a state. Above all else, my island hometown is breathtaking in its scope of natural beauty.

Life on a remote island with a Northern climate meant limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Fortunately, this was offset by the plentiful bounty of both land and sea. It was unheard of to pay for fish or game yet we were up to our eyeballs in salmon, halibut, prawns, crab legs, and venison. When dad wasn’t fishing or hunting himself, family friends generously shared their abundance of glistening filets of salmon and halibut, buckets of salty mussels or five pound bags filled with jumbo spot prawns.

Three of my most memorable childhood meals, if you can call them meals, were prepared by dad, employing little more than a single frying pan and a healthy pat of butter. Each consisted of seafood or game, caught or hunted by my dad or someone he knew. The memories of those meals are unparalleled in my mind, just as they should be.

The most memorable meal is no doubt the first time I tried abalone. If you have never seen an abalone shell, the visual itself is worth a mention. Once all of the meat has been removed, the silvery, rainbow-streaked shells are a sight to behold, with a curved single row of perforations. Think Orion's belt against a backdrop of Aurora Borealis.

Dad knew just what to do with abalone. He reached in the bucket, lifted out a living mollusk and carefully, deliberately pried the the apricot-hued flesh from inside its oval shell. He cleaned it well and used a mallet to tenderize the meat before lightly dredging it with flour and browning it in a pan of sizzling butter.

I sat down at the table, feeling as though I had stepped out of Lewis Carroll’s, The Walrus and the Carpenter, and was presented with a surprisingly small reward for my patience. My teeth sunk into the crisp exterior of that cloud-shaped morsel and I was transported. Nothing in my memory can surpass the butter-laced, delicate sweetness of that taste. Two decades later, on our honeymoon in Kauai, Hawaii, I tried to replicate the experience by ordering abalone at a well established, local seafood restaurant. The results were a far cry from the delicacy my dad had prepared with love so many years ago.

Once, after a successful fishing trip, dad brought home a good-sized rainbow trout. Back then in Alaska, we didn't have to call it 'wild'. It was an assumed trait, the way French fries in France are simply 'pommes frites' (which is French for fried potatoes). Nowadays, it is widely acknowledged that farmed fish threatens the livelihood of commercial fishermen and that 'wild' is undoubtedly the safer, healthier choice. As they say in Alaska, ‘Friends don’t let friends eat farmed fish’.

Dad didn't stray far from simplicity when dealing with fresh fish. He let the food do the talking. As with the abalone, he lightly coated the trout in flour and fried it in butter. After placing the plate before me, he cut a wedge of lemon and trickled the juice over the length of the trout . Forks simultaneously poised, we dove in. The skin was crispy on the outside giving way to bright and buttery tender flesh. Its texture was moist with a delicate firmness. It was the quintessential pan fried wild trout and I have never eaten it since. Whenever I come across trout on a restaurant menu, it is undoubtedly farmed. I came very close to replicating that delectable trout on a visit to Paris, a few years ago. I ordered Sole Meuniere at the legendary bistro, Allard and it was my 'Julia Child moment'. Dad's trout it was not; but this sophisticated city counterpart was akin to that humble yet memorable meal of my childhood.

The last of the three most memorable is one that hasn't exactly taken off in culinary circles. In fact, I am not certain that I would enjoy it as much now as I did then. I know I was very young because I could see the frying pan hovering over the burner, although I had no view of its contents. Dad had just returned from a hunting trip which meant two things. It meant that Mom had gone into hiding until the carnage subsided and it meant that we would be eating venison. I watched as dad cut the meat into small strips then heard the familiar sizzle as it made contact with hot butter in the pan. I smelled the juices emitting from the fragrant meat as it seared. My mouth watered. My brother stood beside me, the two of us waiting, poised like hungry wolves, licking our chops.

Dad had scarcely removed the pan from the flame when his fork made contact with those tendrils of meat, curled up like corkscrews. I popped a piece into my mouth. It was chewy, salty, concentrated in flavor and not at all gamey. Between the three of us, that meat was gone in mere seconds. I demanded more but there was none to be had. I can’t recall whether it was before or after the fact when dad informed us that we had eaten a deer's heart, but it didn’t matter. What I do recall is how proud I felt to embrace my father’s adventurous palate and I knew that I would be telling this story years from that moment.

Mom, with her weak stomach for blood and all things gory, had good reason to hide from the deer slaughtering action. When dad returned from hunting trips, mom would take me somewhere on an 'errand' while he skinned and butchered the deer, which hung from the rafters of our carport. By the time we returned, dad would have cleaned up and all that remained was the faint scent of blood and the smell of fresh venison in the cold air. Not a big fan of cooking or eating wild game, mom tolerated dad's hunting as best she could.

After dad’s return from a successful hunting trip, mom warily approached the driveway, peering over the dash to make sure that the garage was no longer a meat locker. She would pull in only when the coast was clear. On one such occasion, we entered the house and found that all was quiet. I retreated to my bedroom while mom headed for the kitchen to start dinner. Moments later, I was startled by the piercing shriek of a bloodcurdling scream. I rushed to the kitchen where I found mom on the verge of tears, her eyes angrily flashing. Also on the scene were my dad and brother, feigning looks of surprise, which soon gave way to peals of side-aching laughter. In the tall kitchen garbage can, dad had strategically placed a deer's head and legs so that it appeared to be reaching out its hooves and staring straight up at mom when she lifted the lid.

I take great pleasure in passing on dad’s sense of adventure to my six-year-old daughter. Any time that she tries something new or out of the ordinary, we celebrate her efforts by calling grandpa and sharing the good news. Her most adventurous food to date: On our last trip to Paris, we shot this sequence of photos detailing Annabelle’s initial apprehension leading up to her first taste of escargots.

a very good place to start

In my earliest food memory, I was still in a high chair. I have faint recollections of eating baby food and of clamping down on the rubber coated spoon each time mom fed me a bite. That spoon stayed put like ‘The Sword in the Stone’. I remember those spoon wars with a great deal more clarity than what was actually on my plate. The first genuine meal I recall was not the baby food but mom's creamed chipped beef. As if the name doesn't conjure up enough imagery of its own, an online search yields far worse monikers. Mom’s rendition of chipped beef consisted of some variety of highly processed meat, a creamy white sauce and sweet green peas. She topped it off with a snowstorm of crumbled saltines. Not only was this my earliest memory of food, but I was actually quite fond of the stuff. For the early palate, the meal had a lot going for it. Creamy, savory goodness with little peas that popped in the mouth when you bit into them and the satisfying crunch of crumbled saltines. It was the heart and soul of comfort food.

It was comfort food that routinely ruled mom's culinary repertoire. She was devoted to the recipes of her upbringing and rarely strayed from classic dishes such as casseroles, beef stroganoff, stuffed bell peppers, pot roast and spaghetti. Mom was and is an very good cook. Dinner guests were treated to rich beef stew with made from scratch buttermilk biscuits, homemade clam chowder, or marinated flank steak, to name a few. More challenging was the quest to cook food that pleased her family. We were picky eaters and our hard working, self-employed dad was rarely home for a family meal. In addition, our tiny island grocery stores offered limited resources for the home cook.

While mom’s cooking nourished our bellies, her baking made us swoon. She baked gorgeous cakes, toothsome cookies, luscious pies and yeasty loaves of bread. Her reputation as a baker was widespread. I remain partial to her snickerdoodles, apple cake and banana spice bars with lemon icing. She once made an elaborate gingerbread house with stained-glass windows, the works. Another time, mom took cake decorating classes; a period where I consumed unspecified quantities of the lopsided or otherwise imperfect sugar flowers that hadn’t made the cut. My brother and I reaped the benefits of birthday cakes, such as the one below, that were no doubt the envy of every kid in the grade school set.

Deeply ingrained in my memories of childhood is the image of mom with her feet planted firmly in the kitchen. She was either preparing meals, washing dishes or baking something heavenly. Without fail, her baked goods possessed that triple threat: they looked, smelled and tasted out of this world. For mom, baking was nothing short of reassuring. By following the recipe and adding a measure of love to the mix, she would likely yield a result which satisfied her efforts. Baking, in its magical way, transformed ingredients in a way that cooking cooking never could. There was only so much one could do with the wilted produce, frozen foods and canned goods that were the staples of our island diet. The answer to that dilemma? Dessert!

In my post-highchair food memories, I am seated at the hand-me-down poker table that came with our house. Oh, how mom loathed that table. It was covered in Formica with a pattern of black triangular segments separated by faux wood. Worse than the table were the brown pleather swivel chairs accompanying it. What child could ever resist the gravity-defying, whirligig action of a high backed, swiveling dining chair?! It was an amusement park ride at every meal. My brother and I were scolded, reprimanded and probably threatened within an inch of our lives but we could not resist the temptation to make those chairs spin. We did our best to keep mom out of the loop, stealthily spinning whenever her back was turned.

For mom, that poker table and those chairs represented the equivalent of the fishnet stocking-clad leg lamp from 'A Christmas Story'; though my ever frugal dad was no doubt elated at the prospect of free furniture being thrown in when they bought the house. It was many years before we retired the set in favor of something that could only have been a step up. The breaking point may have been initiated by one particular occasion when I decided to whirl my chair as if it would launch me into outer space. It was not the first time I had attempted this feat but it was, regrettably, the time I did so without setting down my Tupperware tumbler, full to the brim with inky purple grape juice. The paint in our dining room proved quite porous and, for a season, our walls took on a look that was decidedly Jackson Pollock.

In time, we bought a respectable dining set and with a new coat of paint our walls lost their mottled purple look. I suspect that the poker table is still making its rounds in my hometown. Furniture rarely leaves the island. I, on the other hand, did.

.jpg)